Every Friday at 5pm, a collective of Indigenous Australians, young and old, jump on a call to discuss the Uluru movement. It’s been a tradition since 2017, when the Uluru Statement from the Heart was established, and continued after the Voice referendum was defeated in October 2023.

They’ve reflected on what went wrong: a highly politicised debate; a rampant disinformation campaign; a cost-of-living crisis that stole attention and triggered fear. And perhaps most significantly, the fact that many Australians didn’t understand the fundamentals of what the referendum was about.

Since then, the Albanese government has backed down on its commitment to real progress on Indigenous issues. “I think [that’s] what happens at a time of acute political loss like a referendum – they’ve gone completely quiet on Aboriginal issues except for Closing the Gap,” says Professor Megan Davis AC, a Cobble Cobble woman and renowned constitutional lawyer. “Closing the Gap is a government program that … doesn’t work, but they still continue it.”

The latest data on the program shows that key targets, including rates of suicide, imprisonment and children in out-of-home care, are continuing to worsen. According to Davis and Aunty Pat Anderson AO, an Alyawarre woman and powerful human rights advocate, the Uluru Statement from the Heart remains as relevant today as ever.

“You don’t just accept no and say that’s the end of it,” says Davis, pointing to a renewed push for a referendum to extend federal government terms from three to four years (Australia voted No on the matter in 1988), and Australia’s long-standing republican movement (Australia voted No in 1999). “No-one tells them to shut up shop.”

Now, with new energy thanks to a rising generation of youth leaders, the Uluru movement is ready to reignite, talk to people about how they voted and listen to their concerns. Notably, 6.2 million Australians voted Yes to a Voice, including an overwhelming majority of Aboriginal Australians.

“About 10 per cent voted No; it was very minuscule,” says Davis. Going forward, the focus on education will be greater and the role of the non-Indigenous “ally” will be different. “We don’t even see them as allies,” says Davis. “We can’t do this separately to them … They need to be walking next to us, not behind us … We want their active input because it’s their democracy and it’s our democracy. One of the lessons of the referendum was that we can’t drive it ourselves. It’s a movement of the Australian people.”

Here, Anderson and Davis take stock of the past and look to the future.

Professor Megan Davis AC The first six months after the referendum were hard. Our biggest concern was how Aboriginal young people felt. They felt ashamed and rejected and a lot of kids got teased at school. That first week, so many people kept their children home.

Aunty Pat Anderson AO It wasn’t a planned thing. It was just what families individually decided, including my nephew who’s a teacher, as is his wife. Even they kept their kids home from school, because it was dangerous.

MD At home they played Aboriginal movies and songs.

PA And had lots of takeaways to keep them comforted. It happened all over the country.

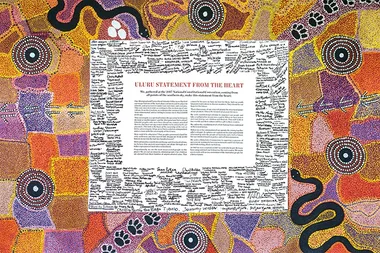

MD There was so much emotion. People had been working on [the campaign] for so long. They were really gutted … I felt like I was forcing everyone to be Pollyannas about the situation instead of letting them be angry. I started reading a lot, trying to figure out [what were] some of the problems. We did essential research. It showed most voters didn’t know what the Uluru Statement from the Heart was. Most didn’t know what the Uluru Dialogues were. And virtually no-one knew that it was an Aboriginal idea and that it wasn’t a politician’s idea, an Albanese idea. When we read that, we were devastated.

PA The referendum was about us, but it was for the nation. It’s not about blackfellas, it’s about who we [Australians] are in the 21st century. What kind of people are we? What are our values? What do we think is important?

MD I think we didn’t get there because it got framed so quickly as a political football. Also, unlike Turnbull and Gillard, Albanese wouldn’t allow us to have non-Indigenous Australians on the committees with us. So it looked like it was a separatist Black issue, and it wasn’t. It was a nation-building one.

PA The people’s movement was never meant to be a political movement.

MD The whole idea was working with Aussies across 151 electorates, actually going and talking to them. They would build the movement because it needs to be us together. And I think the way the referendum process was set up, it was really separative. We had no non-Indigenous faces standing next to us. It looked like it was just a singular Aboriginal thing when in fact it was meant to be an Aussie thing. And that was really lost … politics is like that.

PA The minute we went to Parliament House it went downhill.

MD It’s been two years now and I think people who voted Yes will always be sad about it. And certainly for Aboriginal people, you can see from the AEC ballot results that a majority of Aboriginal people voted Yes – that’s still not very well known by Australians. And in the Northern Territory, every single ballot box voted Yes except for one. And a couple were 90 per cent Yes. I often get emails from No voters saying they had no idea that Aboriginal people wanted the Voice. And that’s partly because the mainstream media elevated No Aboriginal people to the same level as Yes Aboriginal people. But people are regrouping. It was a political loss and we dust ourselves off and we keep going. I think the biggest thing about the [anniversary] is that two years on, statistics are going backwards. Closing the Gap is a mess.

PA Disadvantage for [Indigenous people] across the board is increasing as we speak. Despite the millions, billions, of dollars that goes to the state system, there’s not been a return on what they’ve spent. And now it’s showing, it’s telling. So a lot of money is spent on Aboriginal affairs, but it doesn’t get down to the need, it doesn’t get to [Aboriginal community] Maningrida, where every second or third person is dying of rheumatic heart. It doesn’t get down to the housing shortage. And yet that state jurisdiction has been given money for housing. It doesn’t get there. And nobody says, where did that money go? How many houses did you build? MD Something circulated constantly in the referendum period was that $30 to $40 billion goes into Aboriginal affairs. The number is inaccurate. It was fact-checked, but it didn’t matter in that referendum campaign. The Productivity Commission has come out and said it’s not $30 or $40 billion.

PA It doesn’t come to us.

MD They found around $5 billion actually hits Aboriginal communities. The rest goes to … they count public hospitals; they count all the money that goes to non-Indigenous institutions that is meant to be spent on Aboriginal people; they include money that the Commonwealth uses to fund pastoralist objections to native title; they fund their own litigation against native title. That all gets added to this big number, but it’s not necessarily money that is helping communities. The Productivity Commission is really clear about that, but it doesn’t seem to have permeated the community. So the community thinks all this money going to Aboriginal people is not being effective.

PA Most people just take it for granted that the government’s doing good, Closing the Gap and all that. And then it turns into something like: “All this money that they’re spending on blackfellas and look, they’re still sick, they’re still drunk, they still don’t go to work, and they’re lazy and dirty.” That’s how the argument goes. It’s [nearly] 20 years [of Closing the Gap] and it doesn’t work.

MD There’s an expression, “The purpose of a system is what it does.” And governments are good at that. That is the history of Western liberal democracy and bureaucracies – setting up regulatory frameworks that don’t work. And we see that it’s not just Aboriginal affairs, it’s aged care and nursing homes. It’s little kids in childcare, it’s child protection, it’s the NDIS. We set up these regulatory frameworks and then they don’t function properly.

PA The Voice was going to be the place to [ensure accountability] and ask the state jurisdictions where did that $20 million go? How many houses did you build? Did school enrolments increase? Did you get so many kids this year through year 12 and so on? Nobody [now] would dare ask.

MD A really core part of the Voice would’ve been the cascading impact of having Aboriginal people at the table, not as an afterthought. [A grassroots representative elected by their Indigenous community, as per the Voice] is not the same as [an Aboriginal agency representative selected by the government] living in Canberra saying that they know the problems or saying, “Oh, I’m grassroots. I grew up in an Aboriginal community.” Yeah, but you haven’t been there for 30 years. That’s the difference. Aunty Pat and I grew up in Aboriginal communities, but we wouldn’t be running to represent the Voice in our communities. The point is to get people who are the end users of all the shitty policies that are imposed upon them. They’re the people who don’t have a voice.

PA [That’s why] the Uluru Statement from the Heart is not dead.

MD It’s alive and well. We have so many Aussies contacting us and, weirdly this year, a lot of buyers’ remorse. There’s a slow burn in terms of understanding it. Now, we see our work as building that people’s movement based on what we know now, which is that there’s 6.2 million Australians who get the Voice and who supported it. That’s a huge foundation to build off – we’re not building from zero like we were before the referendum.

And so a big part of what we want to do is get the Yeses to talk to the Nos and have that conversation with Aussies about what Uluru means for our democracy. Because I think if we don’t face up and discuss this issue, it will reemerge with the republic movement. Australia can’t become a republic without recognising First Nations people. You just can’t … So for the past two years we’ve been really reflecting on what went wrong and what we could have done differently. We weren’t expecting the misinformation avalanche at all. Stupidly, I went into it thinking everything was going to be factual. And so I’d be on these radio calls saying the facts, and it’s impossible to have conversations when they’re just throwing stuff at you. “Does this mean the Voice will take the local beach?”

PA They were totally fixated on that … Lots of things have happened, but we certainly haven’t given up. We’ve been doing this since 1788. Why would we give up now? Just because they’ve said no once, or lots of times, really. But the country needs structural reform [across the board]. It needs to reorient, rejig itself and reorganise. A civilised society is judged on how you treat elderly people and how you treat young people. Any society that neglects or mistreats those two sectors of society is not a civilised society. That’s a thumb measure, and Australia bombs out on both categories. MD The royal commissions and commissions of inquiry into child removals, the elderly and people with disability are painting a picture of a community that probably doesn’t do enough to protect these sectors.

PA So the country has to change. We can’t go on like this. Not giving a darn about disadvantaged or poor people, sick people or old people. All the vulnerables, they have to be taken care of. That’s a civilised society. This is a great country, there’s no doubt about that. But we’ve got to do a whole lot better to look after our own people.

MD When people feel included and when they know they’re going to have a voice, they actively engage in democracy. When they feel excluded and their children are being churned into prison, they don’t engage in voting. And these experts throw their hands up and go, but why? It’s because people feel dislocated. And I think part of constitutional recognition is about the nation saying, “We want you to be a part of our democracy.” I know people don’t understand that point, but people don’t feel included in Australian democracy.

PA I don’t think they do.

MD [Professor] Jill Stauffer writes about ethical loneliness. It’s a concept that came out of interviews with men who had been interned in Nazi concentration camps. And it’s a psychological medical phenomenon where people who are so acutely let down by the people who were meant to protect them, they remove themselves from society.

They’re making an ethical decision to protect themselves because humans can’t take being let down over and over again. And so they just dislocate and remove themselves. And you see that manifesting in poor behaviour and poor decisions right across the continent. The belonging aspect is so critical. And I say that partly for my second point, which is that constitutions do provide the material conditions for a good life. Australia’s an affluent country where a majority of people live peaceful lives.

A big part of that is our Constitution, because we have good institutions, we have the rule of law, we have a really good independent High Court system. That has applied to most Australians, which is why most Australians do well, but that doesn’t apply to Aboriginal people because for the first 67 years [after the establishment of Australia’s Constitution], we were excluded completely from the framework. And yes, we had a referendum in 1967 [to count Indigenous Australians in the census and allow the Commonwealth to make laws for them], but it is really difficult to make up that ground in such a short time.

And instead of thinking about the ways in which we can enhance our democracy to make Aboriginal people a part of that democratic framework – given how tiny we are as a cultural group – we are almost entirely blamed for the problems that plague our communities.

And so two years after the referendum, we’re not resigning from the constitutional element [of the Uluru Statement]. The reason still exists for why constitutions can render particular groups more included within the framework of the state. And that’s at the heart of constitutional recognition.

PA The Uluru Statement from the Heart was meant as an olive branch, a message of hope. The invitation is to walk with us, a true, sincere invitation. Come with us. This is your place, too. Learn about it, respect it, love it, and we’ll all be fine.

MD It’s about trying to bring the Aboriginal identity and Australian identity closer, not apart.

This conversation has been edited for length.